2011年02月15日

Art on Honjima

Heading for Honjima

I was off island tripping again recently – this time to Honjima. This island is part of the Shiwaku archipelago, which has played a key role in Japanese maritime transport since ancient times. The currents and shoals around these islands make navigation extremely tricky.

Sunset on the straits off Honjima

Not surprisingly, the people who lived here were expert seamen and navigators. Known as the Shiwaku pirates, they ruled traffic on the Inland Sea. Rather than being in conflict with the authorities, however, they made profitable agreements with them, ferrying goods and granting safe passage. When Japan closed itself to the outside world at the beginning of the 17th century, the ruling Tokugawa shogunate did not maintain its own navy. Instead, they relied on the Shiwaku seamen to provide both shipping and maritime protection. In return, the Shiwaku islanders received full autonomy over their own affairs and were exempt from taxation. When the country was reopened in the mid-19th century, these skilled navigators and sailors also comprised the majority of the crews that sailed the first Japanese ships to America and Europe.

street in Honjima

Honjima (which means “main island”) was the political and economic center of the archipelago and the island retains many historical and cultural assets. Plenty of them are architectural because the island’s shipbuilders doubled as skilled carpenters.

Storehouse (kura) on Honjima

Closeup

When the demand for ships declined after the Meiji era, these carpenters left the island to seek work elsewhere. Consequently, the best shrines and temples constructed in the Shikoku-Chugoku region during this period, as well as the storehouses and merchant buildings in Kurashiki (for which it is now famous), were built by Shiwaku carpenters.

Old clay wall with used roof tiles embedded as fireproofing

storehouse (kura) not yet restored

Fortunately, over 100 exquisite Edo and Meiji period buildings have also been preserved right on Honjima in the Kasashima district. This was my destination and my purpose was to help set up an art exhibit at the Gallery Arte.

Gallery Arte exterior

Interior

Like the other islands in the Seto Inland Sea, Honjima has suffered drastic depopulation. The gallery director, Ikuyo Umetani, relocated here in 2009 with the goal of creating a focal point to draw new people to the aging island and revitalize the community.

Frequent Gallery Arte visitor

Umetani-san has been inviting artists from different parts of Japan to stay and create works for display and sale. While there, the artists also interact with the local community, giving workshops at the school and kindergarten and sharing meals with local residents. (The gallery is also a café serving simple lunches, coffee and wine.)

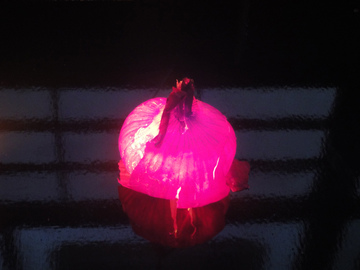

The exhibit running from February through to March 27, 2011 is called Shining Daikon, Sparkling Cabbage and consists of vegetables that light up from within as the viewer walks past. It’s a bit hard to describe but maybe you can get the idea from these photos.

Onion

Cabbage

Leeks

Garlic

If you are an artist and are interested in the artist-in-residence program, check out the following site. The English site hasn’t been updated since last year, but the program is ongoing.

http://en.air-j.info/result/center_37202/

Access Details:

From Shikoku, you can get to Honjima by ferry from Marugame city (30 minutes from Takamatsu by JR train on the Yosan line). The port is under 10 minutes walk from Marugame station. The ferry takes 35 minutes and costs 1,010 yen round trip. (See timetable below provided courtesy of TIA-INFO. If you are coming from Honshu, a ferry leaves from Kojima in Okayama.) Gallery Arte and the historical district are about 10 minutes from Honjima’s port by bicycle, which can be rented when you arrive, and about 20 minutes on foot. Be sure to drop into Kinbansho about halfway to the historical district. This is the former center of island government. It’s a great building and contains such artifacts as 16th century documents bearing the official seal of Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Kinbansho

Gallery ARTE

Hours: 11:30-16:30 Closed on Mon. and Tue. (Open if those days are holidays)

Admission: Free

Exhibit: Feb.2-Mar. 27, 2011, “Shining Daikon, Sparkling Cabbage” - Yuichi Hirano

Café

Kimagure lunch from JPY 600 to JPY 750.

Pasta/pizza JPY1000.

Kanrinmaru lunch JPY1,500 (reservation required for this particular meal but not for others).

Address:

305 Kasajima Honjima, Marugame-shi, Kagawa

Tel: 0877-57-8255 / e-mail: arte@mti.biglobe.ne.jp

Web: http://www5a.biglobe.ne.jp/~Arte2000/index.html

My Profile

Cathy Hirano キャシー ヒラノ

I've lived in Japan since 1978. After graduating from a Japanese university with a BA in cultural anthropology in 1983, I worked as a translator in a Japanese consulting engineering firm in Tokyo for several years. My Japanese husband and I moved to Takamatsu in 1987 to raise our two children in a slower-paced environment away from the big city pressures. We've never regretted it. I work as a freelance translator and interpreter and am involved in a lot of community work, including volunteering for Second Hand, a local NGO that supports educational and vocational training initiatives in Cambodia, and for the Takamatsu International Association. I love living in Takamatsu.

Cathy Hirano キャシー ヒラノ

I've lived in Japan since 1978. After graduating from a Japanese university with a BA in cultural anthropology in 1983, I worked as a translator in a Japanese consulting engineering firm in Tokyo for several years. My Japanese husband and I moved to Takamatsu in 1987 to raise our two children in a slower-paced environment away from the big city pressures. We've never regretted it. I work as a freelance translator and interpreter and am involved in a lot of community work, including volunteering for Second Hand, a local NGO that supports educational and vocational training initiatives in Cambodia, and for the Takamatsu International Association. I love living in Takamatsu.

Posted by cathy at 10:09│Comments(4)

│art

この記事へのコメント

Great and instructive post Cathy. The more I read about the Seto islands, the more I love them. :-)

You mentioned "pirates" and it made me think. I often heard about pirates on Megijima (living in the Oni cave) and Ogijima (with some of the houses built in a way to make them easy to protect against pirates). Would you happen to know more about those pirates? Would they be the Shiwaku people? The way you describe them, I seriously doubt it.

In any case, one more island I need to visit for my next trip. :-)

You mentioned "pirates" and it made me think. I often heard about pirates on Megijima (living in the Oni cave) and Ogijima (with some of the houses built in a way to make them easy to protect against pirates). Would you happen to know more about those pirates? Would they be the Shiwaku people? The way you describe them, I seriously doubt it.

In any case, one more island I need to visit for my next trip. :-)

Posted by David at 2011年02月16日 02:24

Hi David,

I had the same question as you but haven't found any answers yet. The Shiwaku islands includes Ogijima so you would think the pirates would not be robbing their home ground. At the same time, however, their unique system of government invested marine rights to only 650 people. A council of elders was then chosen from a few select families within this group and they ruled the islands. The rights were passed down from one generation to the next. Ordinary people who lived on Shiwaku islands had to get permission and sometimes pay for the right to fish, etc. From the documents I read, the people with rights discriminated quite strongly against those without. Another point to consider is that there were other groups called "pirates" (kaizoku) in different parts of Japan. They all raided Japan as well as other areas. I wonder if the term "pirates" even really means the same thing in Japanese as in English. The Japanse kaizoku seems to have been a family occupation like fishing or farming, a trade that people passed onto their children. Anyway, If I find out anything more, I'll let you know.

I had the same question as you but haven't found any answers yet. The Shiwaku islands includes Ogijima so you would think the pirates would not be robbing their home ground. At the same time, however, their unique system of government invested marine rights to only 650 people. A council of elders was then chosen from a few select families within this group and they ruled the islands. The rights were passed down from one generation to the next. Ordinary people who lived on Shiwaku islands had to get permission and sometimes pay for the right to fish, etc. From the documents I read, the people with rights discriminated quite strongly against those without. Another point to consider is that there were other groups called "pirates" (kaizoku) in different parts of Japan. They all raided Japan as well as other areas. I wonder if the term "pirates" even really means the same thing in Japanese as in English. The Japanse kaizoku seems to have been a family occupation like fishing or farming, a trade that people passed onto their children. Anyway, If I find out anything more, I'll let you know.

Posted by cathy at 2011年02月17日 10:17

David,

Check out the following site.

http://www.historycooperative.org/proceedings/seascapes/shapinsky.html

It's a good study on how the pirates operated. My understanding is that the Murakami suigun pirates the author examines in this paper were the dominant force in the Inland Sea up until the late 16th century and that for some of that time they controlled the Shiwaku islands as well. But they were on the losing side during the final power struggle that led to the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa SHogunate. The Shiwaku marine force, on the other hand, assissted the winning side and so were awarded autonomy, tax exemption and the right to ferry goods, fish, trade, etc. in the Inland Sea. These rights were called ninmyo kabu and my understanding is that they were awarded to the 650 people directly involved as allies. I am not 100% sure about these facts and this doesn't answer your question about what pirates were still raiding Ogijima in the 19th century but I'll keep looking.

Check out the following site.

http://www.historycooperative.org/proceedings/seascapes/shapinsky.html

It's a good study on how the pirates operated. My understanding is that the Murakami suigun pirates the author examines in this paper were the dominant force in the Inland Sea up until the late 16th century and that for some of that time they controlled the Shiwaku islands as well. But they were on the losing side during the final power struggle that led to the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa SHogunate. The Shiwaku marine force, on the other hand, assissted the winning side and so were awarded autonomy, tax exemption and the right to ferry goods, fish, trade, etc. in the Inland Sea. These rights were called ninmyo kabu and my understanding is that they were awarded to the 650 people directly involved as allies. I am not 100% sure about these facts and this doesn't answer your question about what pirates were still raiding Ogijima in the 19th century but I'll keep looking.

Posted by cathy at 2011年02月18日 14:54

Thanks a lot...

I've just recently started learning more about Japan's history and it's so fascinating.

:-)

I've just recently started learning more about Japan's history and it's so fascinating.

:-)

Posted by David at 2011年02月21日 10:01

※会員のみコメントを受け付けております、ログインが必要です。