2010年11月25日

The Last Word

The Last Word On Setouchi Art Festival 2010

Curious about the festival’s impact on the islands and on people, I have been talking with local artists and friends involved in the festival as well as others like me who experienced it.

Seto Inland Sea

According to my sources, while many islanders warmly welcomed the visitors, they are now breathing a sigh of relief. The party is over and they are happy to return to the slower pace of “island time”.

Island time on Teshima

During the festival, particularly on weekends and through most of October, some villages were so crowded that local residents had difficulty just walking down the street to get home. And, unfortunately, some people left their garbage behind.

On the bright side, the islanders realized that people actually enjoyed coming to their islands. Left behind by mainstream society, their backwater villages are now on the brink of disappearing but the festival demonstrated that they do indeed have charm and potential. The question is where to go from here.

Teshima

If nothing else, Art Setouchi has forced those directly involved as well as those who just live here to ponder this very question. Further action, particularly by the islanders, is needed to explore the opportunities provided by the festival. Ideally, each island will develop their own style of collaboration with other people living in the prefecture as well as with artists – a collaboration that promotes sustainable action.

Lightening Shodoshima by Sense Art Studio

As a local and frequent visitor to the festival, I would have to say that it was nothing but positive. It gave me a chance to experience and appreciate the beauty of what we have. It also, as one friend aptly put it, served as a medium for people to make meaningful connections, with each other and with art and nature. What kept so many people going back? In their words…

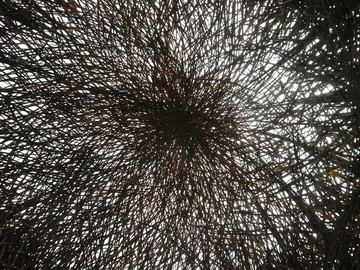

Farther Memory by Chiharu Shiota

… art in architecture/architecture in art

Project by Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts and Music Team

… being able to walk right into an exhibit

House of Shodoshima by Wang Wen-Chih

and enjoy it like this

inside

and out!

…art in nature/nature in art

When You Think of an Island by Rika Aki, Shodoshima

…having the time to listen

…to voices whispering through bamboo pipes

Voices from Disappeared People by Dadang Christanto, Shodoshima

…and seashells quivering by a spring.

When You Think of an Island by Rika Aki, Shodoshima

… strange and wonderful encounters, such as walking through terraced rice fields in the middle of nowhere

and bumping into a friend from Tokyo.

Art within the ordinary made life extraordinary.

Hello Hachijuro by Hiroshi Fuji, Teshima

Ichigoya’s homemade strawberry sauce on ice, Teshima

And it was just so much fun!

For those of you who can, I hope you will consider going back to the islands on weekends and checking out the sites that are still open. The volunteers bravely manning the sites will be very glad to see you! If you don’t have a Japanese friend to read the schedules for you (See previous post), post a comment about where and when you want to go and I’ll let you know if it’s open.

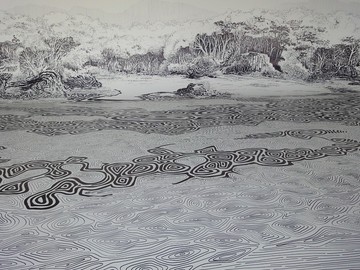

For fans of Brazilian artist Oscar Oiwa

Oiwa Island, an amazing work drawn entirely with black magic markers and transformed into an endless landscape by mirrors, was sadly destroyed in a fire one month before the festival ended.

The work, however, has been awarded the festival’s grand prize. Many artists participated in the festival by invitation but some were chosen through a public screening process. Out of 721 entries, 20 artists were selected, and out of those, Oiwa’s Island won the prize. This grants the artist the right to participate in the next festival. We’ll look forward to seeing more of Oiwa’s work in Kagawa!

*Check out Oscar Oiwa’s site below to see a great video on the process of creating Oiwa’s Island.

http://www.oscaroiwastudio.com/oscar_website/pages.html/news.html

Video can also be accessed here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zr59vzndrcU

Curious about the festival’s impact on the islands and on people, I have been talking with local artists and friends involved in the festival as well as others like me who experienced it.

Seto Inland Sea

According to my sources, while many islanders warmly welcomed the visitors, they are now breathing a sigh of relief. The party is over and they are happy to return to the slower pace of “island time”.

Island time on Teshima

During the festival, particularly on weekends and through most of October, some villages were so crowded that local residents had difficulty just walking down the street to get home. And, unfortunately, some people left their garbage behind.

On the bright side, the islanders realized that people actually enjoyed coming to their islands. Left behind by mainstream society, their backwater villages are now on the brink of disappearing but the festival demonstrated that they do indeed have charm and potential. The question is where to go from here.

Teshima

If nothing else, Art Setouchi has forced those directly involved as well as those who just live here to ponder this very question. Further action, particularly by the islanders, is needed to explore the opportunities provided by the festival. Ideally, each island will develop their own style of collaboration with other people living in the prefecture as well as with artists – a collaboration that promotes sustainable action.

Lightening Shodoshima by Sense Art Studio

As a local and frequent visitor to the festival, I would have to say that it was nothing but positive. It gave me a chance to experience and appreciate the beauty of what we have. It also, as one friend aptly put it, served as a medium for people to make meaningful connections, with each other and with art and nature. What kept so many people going back? In their words…

Farther Memory by Chiharu Shiota

… art in architecture/architecture in art

Project by Aichi Prefectural University of Fine Arts and Music Team

… being able to walk right into an exhibit

House of Shodoshima by Wang Wen-Chih

and enjoy it like this

inside

and out!

…art in nature/nature in art

When You Think of an Island by Rika Aki, Shodoshima

…having the time to listen

…to voices whispering through bamboo pipes

Voices from Disappeared People by Dadang Christanto, Shodoshima

…and seashells quivering by a spring.

When You Think of an Island by Rika Aki, Shodoshima

… strange and wonderful encounters, such as walking through terraced rice fields in the middle of nowhere

and bumping into a friend from Tokyo.

Art within the ordinary made life extraordinary.

Hello Hachijuro by Hiroshi Fuji, Teshima

Ichigoya’s homemade strawberry sauce on ice, Teshima

And it was just so much fun!

For those of you who can, I hope you will consider going back to the islands on weekends and checking out the sites that are still open. The volunteers bravely manning the sites will be very glad to see you! If you don’t have a Japanese friend to read the schedules for you (See previous post), post a comment about where and when you want to go and I’ll let you know if it’s open.

For fans of Brazilian artist Oscar Oiwa

Oiwa Island, an amazing work drawn entirely with black magic markers and transformed into an endless landscape by mirrors, was sadly destroyed in a fire one month before the festival ended.

The work, however, has been awarded the festival’s grand prize. Many artists participated in the festival by invitation but some were chosen through a public screening process. Out of 721 entries, 20 artists were selected, and out of those, Oiwa’s Island won the prize. This grants the artist the right to participate in the next festival. We’ll look forward to seeing more of Oiwa’s work in Kagawa!

*Check out Oscar Oiwa’s site below to see a great video on the process of creating Oiwa’s Island.

http://www.oscaroiwastudio.com/oscar_website/pages.html/news.html

Video can also be accessed here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zr59vzndrcU

2010年11月24日

Summing Up

Summing Up Art Setouchi

The Setouchi International Art Festival was supposed to end on October 31. And it did, but it proved so successful that the prefecture has decided to go ahead with the original plan of hosting another festival in three years.

Jumping for joy on Megijima

In addition, many of the sites that were to be shut down and dismantled are being kept open for a few more months. A total of 42 sites* will be open, at least on weekends. Extra ferries and island buses will also be kept running experimentally to see if there is enough local demand to make their continuation worthwhile.

Seagull Parking Lot, Takahito Kimura, Megijima

So just how successful was it? In June, the organizers anticipated the festival would attract about 300,000 visitors with an economic benefit of about 5 billion yen. In fact, however, the festival attracted over 938, 000 visitors with an economic benefit of close to 15 billion yen. Wow!!!

Happy travelers on Teshima

The biggest financial winners were probably the ferry companies. Ferries were filled to capacity even with extra sailings to keep up with demand. Ferries to Megijima and Ogijima islands, for example, had 2.4 times more passengers than usual, causing the company to scrap its plans for selling off one of its boats.

The Meon docking at Ogijima

Hotels near Takamatsu station enjoyed twice as many customers as usual and clientele expanded to include families, students and foreigners in addition to businessmen. Local and festival-related souvenir shops also did a brisk business.

Ogijima’s Soul by Jaume Plensa

Nothing is perfect however and a number of things need to be addressed before the next festival. For example, one of Art Setouchi’s greatest attractions was being forced to slow down to “island time”. Billed as an “art adventure”, exploring these out-of-the-way islands and ‘discovering’ art was really fun!! But once the word spread, the area was deluged with people.

Ferry line up at Inujima stretching off out of sight.

About 500,000 visitors descended on the festival in October alone, more than had come in the first 2 months combined! This stretched transportation, accommodation and art facilities to the limit. It was the hardworking volunteer staff, the islanders’ spirit of hospitality and the patience of visitors that carried the festival through this overload.

Helping each other out on Ogijima

While some locations reaped economic benefits from this huge influx of people, many local tourist attractions did not. For example, the number of visitors to my favorite Takamatsu spot, Ritsurin Garden, (see http://cathy.ashita-sanuki.jp/e229240.html ) dropped to 87% of the norm in August and to 63% in September, even though it’s very accessible. The festival seems to have caught many local organizations and businesses by surprise and they were too late to take advantage of the opportunity. If they are going to link up with the next festival, they need to be involved from the planning stage.

The real measure of the festival’s success, however, must be its impact on the islands and on us, a subject I will look at in my next article.

*Note:

The fact that many sites are still open has been very under-publicized. Fortunately, despite this, some people are going back, glad to be able to enjoy the remaining sites at their leisure. If you are visiting or live here, go and check them out.

Sites open through to the end of December 2010 are listed here (Japanese only):

http://setouchi-artfest.jp/images/uploads/misc/artworks_20101101_20101231r.pdf

Sites open January through to the end of March 2011 are listed here (Japanese only):

http://setouchi-artfest.jp/images/uploads/misc/artworks_20110101_20110131.pdf

* Many thanks to Kazumi, Hiroko, Reina, Kento and Pat for sharing photos for this and the next article.

The Setouchi International Art Festival was supposed to end on October 31. And it did, but it proved so successful that the prefecture has decided to go ahead with the original plan of hosting another festival in three years.

Jumping for joy on Megijima

In addition, many of the sites that were to be shut down and dismantled are being kept open for a few more months. A total of 42 sites* will be open, at least on weekends. Extra ferries and island buses will also be kept running experimentally to see if there is enough local demand to make their continuation worthwhile.

Seagull Parking Lot, Takahito Kimura, Megijima

So just how successful was it? In June, the organizers anticipated the festival would attract about 300,000 visitors with an economic benefit of about 5 billion yen. In fact, however, the festival attracted over 938, 000 visitors with an economic benefit of close to 15 billion yen. Wow!!!

Happy travelers on Teshima

The biggest financial winners were probably the ferry companies. Ferries were filled to capacity even with extra sailings to keep up with demand. Ferries to Megijima and Ogijima islands, for example, had 2.4 times more passengers than usual, causing the company to scrap its plans for selling off one of its boats.

The Meon docking at Ogijima

Hotels near Takamatsu station enjoyed twice as many customers as usual and clientele expanded to include families, students and foreigners in addition to businessmen. Local and festival-related souvenir shops also did a brisk business.

Ogijima’s Soul by Jaume Plensa

Nothing is perfect however and a number of things need to be addressed before the next festival. For example, one of Art Setouchi’s greatest attractions was being forced to slow down to “island time”. Billed as an “art adventure”, exploring these out-of-the-way islands and ‘discovering’ art was really fun!! But once the word spread, the area was deluged with people.

Ferry line up at Inujima stretching off out of sight.

About 500,000 visitors descended on the festival in October alone, more than had come in the first 2 months combined! This stretched transportation, accommodation and art facilities to the limit. It was the hardworking volunteer staff, the islanders’ spirit of hospitality and the patience of visitors that carried the festival through this overload.

Helping each other out on Ogijima

While some locations reaped economic benefits from this huge influx of people, many local tourist attractions did not. For example, the number of visitors to my favorite Takamatsu spot, Ritsurin Garden, (see http://cathy.ashita-sanuki.jp/e229240.html ) dropped to 87% of the norm in August and to 63% in September, even though it’s very accessible. The festival seems to have caught many local organizations and businesses by surprise and they were too late to take advantage of the opportunity. If they are going to link up with the next festival, they need to be involved from the planning stage.

The real measure of the festival’s success, however, must be its impact on the islands and on us, a subject I will look at in my next article.

*Note:

The fact that many sites are still open has been very under-publicized. Fortunately, despite this, some people are going back, glad to be able to enjoy the remaining sites at their leisure. If you are visiting or live here, go and check them out.

Sites open through to the end of December 2010 are listed here (Japanese only):

http://setouchi-artfest.jp/images/uploads/misc/artworks_20101101_20101231r.pdf

Sites open January through to the end of March 2011 are listed here (Japanese only):

http://setouchi-artfest.jp/images/uploads/misc/artworks_20110101_20110131.pdf

* Many thanks to Kazumi, Hiroko, Reina, Kento and Pat for sharing photos for this and the next article.

2010年11月08日

TheGentleArtProject Revisited2

Setouchi International Art Festival

Oshima Revisited: The Gentle Art Project * Part 2

Highlights

Those of us lucky enough to go to Oshima during the festival were given a 60-minute guided tour and then allowed to wander in designated places that did not intrude on the residents’ privacy if there was any time left over. The guides gave an extremely well informed account of the sanatorium’s history and the people who live here. Because there are few records, these volunteers actually gathered much of the information directly from local residents. This type of interaction with the islanders was a key part of the project. Using art as a medium, the project captured the attention of people who had been unaware of the residents’ plight and helped residents and visitors take a step towards ending social isolation.

Our first stop was a memorial building that houses cinerary urns containing the ashes of the deceased. We said prayers at the altar outside.

Roof of memorial building viewed from the pier.

The day I went, we were extremely fortunate to be invited inside the building, which had been opened for a special group. The interior is lined with glass cases filled with more than 2,000 small cinerary urns carefully wrapped in beautiful brocade. The respect shown in this room seemed to me to reflect the positive change in society’s attitude towards its former outcasts.

The monuments in the photo below told us more of the islanders’ story.

Stone monuments.

If someone had Hansen’s disease and was sent to a sanatorium, the rest of the family hid that fact for fear of social ostracism. The person was considered already dead and therefore no one went to collect his or her ashes when they actually passed away. In the photo above, the monument on the left is dedicated to over 600 early residents and contains the ashes and bones that did not go into the urns. The monument in the middle is dedicated to the souls of the residents’ unborn children. Couples who married were sterilized but sometimes the operation failed, resulting in pregnancy. In that case, the child had to be aborted. The stone on the right is dedicated to the first medical doctor to become sanatorium director. I was surprised to see that he was treated so specially until our guide explained that previous directors had been from the police department. It really brought home the fact that the early sanatoriums were not built to help or cure the residents but to prevent them from escaping back to the “normal” world.

View of Ogijima back right (Photo by Kazumi)

Life was so hard in the early decades that quite a few residents did in fact attempt to escape by swimming across to other islands only to be caught and returned. They would be heading towards islands like Ogijima, the one in the far distance in the above photo. Considering the tides and the distance, it would not be an easy swim so the escapees must have been pretty desperate. Some did not make it while others did not try. They simply committed suicide by jumping in the sea. The bodies washing up on nearby shores probably deepened the fear and prejudice of local people who lived near Oshima. Living conditions on the island, particularly in the early years, were harsh, with 12 people living in 24-mat rooms (about 3 square meters/person), each with only a tiny wooden cupboard to store their few belongings. Obviously, there was no privacy. Inmates included children with leprosy or children exiled with parents who had leprosy. Some of the sanatorium employees also had children so that at one point there were three schools to segregate the different children and the island was divided into yūdoku (“toxic”) and mudoku (“non-toxic”) zones. Conditions gradually improved and each resident now has a small one-room apartment with a kitchen, a closet and a separate entrance, plus some space outside for gardening.

Resident’s impressive bonsai garden.

The sanatorium tried to be as self-sufficient in food production as possible. The residents thus grew much of their own food and there are still small vegetable plots on the island. From the bonsai collection in the photo above, you can see that some residents really take pride in their gardening skills.

White lines

The disease has impaired the eyesight of many residents. White lines on the road help them find their way and they can also tap their canes along the metal railings that line the roadside. Speakers at every intersection play music to help them keep their bearings.

Speaker and railing

Shikoku has a centuries-old pilgrimage route to 88 temples around the entire island. It takes a few months to complete on foot. These 88 temples each donated a statue to the island so that residents could complete the pilgrimage without leaving Oshima.

Buddhist statue donated by Zentsuji Temple, home of Kobo Daishi, the pilgrimage route foundering

In 1992, a thousand volunteers and residents worked together to create the monument below. Called Kaze no mai or “Wind Dance”, it is located behind the crematorium and contains the leftover ashes and bones of more recent residents. The name represents the islanders’ hope that at least in death they can be set free and return to their homelands.

Wind Dance monument (photos by Kazumi)

Wind Dance was built before the segregation law was repealed and it stands as a testimony to the fact that many people had been advocating the rights of sanatorium residents long before the laws changed. The monument and the art project serve as excellent reminders that changes for the better are brought about by ordinary citizens who care; by people who see beyond such differences as “disability”, “race” or “gender” to the common humanity in the heart of each one of us and are willing to stand up against injustice.

The festival ended on October 31, 2010. I am hoping that the project will continue in some form or other because it provided a great vehicle for Oshima residents and “outsiders” to come together as fellow human beings. The festival’s Japanese website says that it will at least open again for a few days in December but the details are still under discussion. Once decided the details will be posted on the Japanese festival website: http://setouchi-artfest.jp/

Here also is the list of sites that will stay open until Dec. 31:

http://setouchi-artfest.jp/images/uploads/misc/artworks_20101101_20101231r.pdf

It is still possible to visit Oshima regardless of the festival and the boat is free but you need to contact the National Sanatorium Oshima Seishoen to get permission. The phone number is 087-871-3131 (Japanese only). The facility offers a tour of the sanatorium that includes a talk by the facility doctor and time to interact with the residents (again in Japanese). You can arrange to take a group or, if you are going with only a few people, you can arrange to be included in another group’s tour. Call the facility to ask for a suitable date and time and then send a letter addressed to the director stating when you are going. The boat timetable is here:

http://www.hosp.go.jp/~osima/timetable/H221001~H230331.pdf

The Japanese website is here: http://www.hosp.go.jp/~osima/index1.html

I know for many of you this will involve getting a Japanese person to help you but it is worth the effort.

*Again, many thanks to art project director Nobuyuki Takahashi and the Koebitai volunteers for so much helpful information.

View looking out from Oshima.

Oshima Revisited: The Gentle Art Project * Part 2

Highlights

Those of us lucky enough to go to Oshima during the festival were given a 60-minute guided tour and then allowed to wander in designated places that did not intrude on the residents’ privacy if there was any time left over. The guides gave an extremely well informed account of the sanatorium’s history and the people who live here. Because there are few records, these volunteers actually gathered much of the information directly from local residents. This type of interaction with the islanders was a key part of the project. Using art as a medium, the project captured the attention of people who had been unaware of the residents’ plight and helped residents and visitors take a step towards ending social isolation.

Our first stop was a memorial building that houses cinerary urns containing the ashes of the deceased. We said prayers at the altar outside.

Roof of memorial building viewed from the pier.

The day I went, we were extremely fortunate to be invited inside the building, which had been opened for a special group. The interior is lined with glass cases filled with more than 2,000 small cinerary urns carefully wrapped in beautiful brocade. The respect shown in this room seemed to me to reflect the positive change in society’s attitude towards its former outcasts.

The monuments in the photo below told us more of the islanders’ story.

Stone monuments.

If someone had Hansen’s disease and was sent to a sanatorium, the rest of the family hid that fact for fear of social ostracism. The person was considered already dead and therefore no one went to collect his or her ashes when they actually passed away. In the photo above, the monument on the left is dedicated to over 600 early residents and contains the ashes and bones that did not go into the urns. The monument in the middle is dedicated to the souls of the residents’ unborn children. Couples who married were sterilized but sometimes the operation failed, resulting in pregnancy. In that case, the child had to be aborted. The stone on the right is dedicated to the first medical doctor to become sanatorium director. I was surprised to see that he was treated so specially until our guide explained that previous directors had been from the police department. It really brought home the fact that the early sanatoriums were not built to help or cure the residents but to prevent them from escaping back to the “normal” world.

View of Ogijima back right (Photo by Kazumi)

Life was so hard in the early decades that quite a few residents did in fact attempt to escape by swimming across to other islands only to be caught and returned. They would be heading towards islands like Ogijima, the one in the far distance in the above photo. Considering the tides and the distance, it would not be an easy swim so the escapees must have been pretty desperate. Some did not make it while others did not try. They simply committed suicide by jumping in the sea. The bodies washing up on nearby shores probably deepened the fear and prejudice of local people who lived near Oshima. Living conditions on the island, particularly in the early years, were harsh, with 12 people living in 24-mat rooms (about 3 square meters/person), each with only a tiny wooden cupboard to store their few belongings. Obviously, there was no privacy. Inmates included children with leprosy or children exiled with parents who had leprosy. Some of the sanatorium employees also had children so that at one point there were three schools to segregate the different children and the island was divided into yūdoku (“toxic”) and mudoku (“non-toxic”) zones. Conditions gradually improved and each resident now has a small one-room apartment with a kitchen, a closet and a separate entrance, plus some space outside for gardening.

Resident’s impressive bonsai garden.

The sanatorium tried to be as self-sufficient in food production as possible. The residents thus grew much of their own food and there are still small vegetable plots on the island. From the bonsai collection in the photo above, you can see that some residents really take pride in their gardening skills.

White lines

The disease has impaired the eyesight of many residents. White lines on the road help them find their way and they can also tap their canes along the metal railings that line the roadside. Speakers at every intersection play music to help them keep their bearings.

Speaker and railing

Shikoku has a centuries-old pilgrimage route to 88 temples around the entire island. It takes a few months to complete on foot. These 88 temples each donated a statue to the island so that residents could complete the pilgrimage without leaving Oshima.

Buddhist statue donated by Zentsuji Temple, home of Kobo Daishi, the pilgrimage route foundering

In 1992, a thousand volunteers and residents worked together to create the monument below. Called Kaze no mai or “Wind Dance”, it is located behind the crematorium and contains the leftover ashes and bones of more recent residents. The name represents the islanders’ hope that at least in death they can be set free and return to their homelands.

Wind Dance monument (photos by Kazumi)

Wind Dance was built before the segregation law was repealed and it stands as a testimony to the fact that many people had been advocating the rights of sanatorium residents long before the laws changed. The monument and the art project serve as excellent reminders that changes for the better are brought about by ordinary citizens who care; by people who see beyond such differences as “disability”, “race” or “gender” to the common humanity in the heart of each one of us and are willing to stand up against injustice.

The festival ended on October 31, 2010. I am hoping that the project will continue in some form or other because it provided a great vehicle for Oshima residents and “outsiders” to come together as fellow human beings. The festival’s Japanese website says that it will at least open again for a few days in December but the details are still under discussion. Once decided the details will be posted on the Japanese festival website: http://setouchi-artfest.jp/

Here also is the list of sites that will stay open until Dec. 31:

http://setouchi-artfest.jp/images/uploads/misc/artworks_20101101_20101231r.pdf

It is still possible to visit Oshima regardless of the festival and the boat is free but you need to contact the National Sanatorium Oshima Seishoen to get permission. The phone number is 087-871-3131 (Japanese only). The facility offers a tour of the sanatorium that includes a talk by the facility doctor and time to interact with the residents (again in Japanese). You can arrange to take a group or, if you are going with only a few people, you can arrange to be included in another group’s tour. Call the facility to ask for a suitable date and time and then send a letter addressed to the director stating when you are going. The boat timetable is here:

http://www.hosp.go.jp/~osima/timetable/H221001~H230331.pdf

The Japanese website is here: http://www.hosp.go.jp/~osima/index1.html

I know for many of you this will involve getting a Japanese person to help you but it is worth the effort.

*Again, many thanks to art project director Nobuyuki Takahashi and the Koebitai volunteers for so much helpful information.

View looking out from Oshima.